- Home

- W. E. B. Du Bois

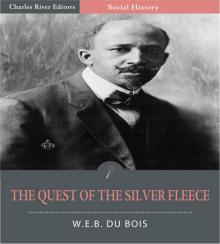

The Quest of the Silver Fleece: A Novel Page 7

The Quest of the Silver Fleece: A Novel Read online

Page 7

_Six_

COTTON

The cry of the naked was sweeping the world. From the peasant toiling inRussia, the lady lolling in London, the chieftain burning in Africa, andthe Esquimaux freezing in Alaska; from long lines of hungry men, frompatient sad-eyed women, from old folk and creeping children went up thecry, "Clothes, clothes!" Far away the wide black land that belts theSouth, where Miss Smith worked and Miss Taylor drudged and Bles and Zoradreamed, the dense black land sensed the cry and heard the bound ofanswering life within the vast dark breast. All that dark earth heavedin mighty travail with the bursting bolls of the cotton while blackattendant earth spirits swarmed above, sweating and crooning to itsbirth pains.

After the miracle of the bursting bolls, when the land was brightestwith the piled mist of the Fleece, and when the cry of the naked wasloudest in the mouths of men, a sudden cloud of workers swarmed betweenthe Cotton and the Naked, spinning and weaving and sewing and carryingthe Fleece and mining and minting and bringing the Silver till the Songof Service filled the world and the poetry of Toil was in the souls ofthe laborers. Yet ever and always there were tense silent white-facedmen moving in that swarm who felt no poetry and heard no song, and oneof these was John Taylor.

He was tall, thin, cold, and tireless and he moved among the Watchers ofthis World of Trade. In the rich Wall Street offices of Grey andEasterly, Brokers, Mr. Taylor, as chief and confidential clerk surveyedthe world's nakedness and the supply of cotton to clothe it. The objectof his watching was frankly stated to himself and to his world. Hepurposed going into business neither for his own health nor for thehealing or clothing of the peoples but to apply his knowledge of theworld's nakedness and of black men's toil in such a way as to bringhimself wealth. In this he was but following the teaching of his highestideal, lately deceased, Mr. Job Grey. Mr. Grey had so successfullymanipulated the cotton market that while black men who made the cottonstarved in Alabama and white men who bought it froze in Siberia, hehimself sat--

_"High on a throne of royal state That far outshone the wealth Of Ormuz or of Ind._"

Notwithstanding this he died eventually, leaving the burden of hiswealth to his bewildered wife, and his business to the astute Mr.Easterly; not simply to Mr. Easterly, but in a sense to his spiritualheir, John Taylor.

To be sure Mr. Taylor had but a modest salary and no financial interestin the business, but he had knowledge and business daring--effronteryeven--and the determination was fixed in his mind to be a millionaire atno distant date. Some cautious fliers on the market gave him enoughsurplus to send his sister Mary through the high school of his countryhome in New Hampshire, and afterward through Wellesley College; althoughjust why a woman should want to go through college was inexplicable toJohn Taylor, and he was still uncertain as to the wisdom of his charity.

When she had an offer to teach in the South, John Taylor hurried her offfor two reasons: he was profoundly interested in the cotton-belt, andthere she might be of service to him; and secondly, he had spent all themoney on her that he intended to at present, and he wanted her to go towork. As an investment he did not consider Mary a success. Her lettersintimated very strongly her intention not to return to Miss Smith'sSchool; but they also brought information--disjointed and incomplete, tobe sure--which mightily interested Mr. Taylor and sent him to atlases,encyclopaedias, and census-reports. When he went to that little lunchwith old Mrs. Grey he was not sure that he wanted his sister to leavethe cotton-belt just yet. After lunch he was sure that he did not wanther to leave.

The rich Mrs. Grey was at the crisis of her fortunes. She was an elderlylady, in those uncertain years beyond fifty, and had been left suddenlywith more millions than she could easily count. Personally she wasinclined to spend her money in bettering the world right off, in suchways as might from time to time seem attractive. This course, to herhusband's former partner and present executor, Mr. Edward Easterly, wasnot only foolish but wicked, and, incidentally, distinctly unprofitableto him. He had expressed himself strongly to Mrs. Grey last night atdinner and had reinforced his argument by a pointed letter written thismorning.

To John Taylor Mrs. Grey's disposal of the income was unbelievableblasphemy against the memory of a mighty man. He did not put this inwords to Mrs. Grey--he was only head clerk in her late husband'soffice--but he became watchful and thoughtful. He ate his soup insilence when she descanted on various benevolent schemes.

"Now, what do you know," she asked finally, "about Negroes--abouteducating them?" Mr. Taylor over his fish was about to deny allknowledge of any sort on the subject, but all at once he recollected hissister, and a sudden gleam of light radiated his mental gloom.

"Have a sister who is--er--devoting herself to teaching them," he said.

"Is that so!" cried Mrs. Grey, joyfully. "Where is she?"

"In Tooms County, Alabama--in--" Mr. Taylor consulted a remote mentalpocket--"in Miss Sara Smith's school."

"Why, how fortunate! I'm so glad I mentioned the matter. You see, MissSmith is a sister of a friend of ours, Congressman Smith of New Jersey,and she has just written to me for help; a very touching letter, too,about the poor blacks. My father set great store by blacks and was aleading abolitionist before he died."

Mr. Taylor was thinking fast. Yes, the name of Congressman Peter Smithwas quite familiar. Mr. Easterly, as chairman of the Republican StateCommittee of New Jersey, had been compelled to discipline Mr. Smithpretty severely for certain socialistic votes in the House, andconsequently his future career was uncertain. It was important that sucha man should not have too much to do with Mrs. Grey's philanthropies--atleast, in his present position.

"Should like to have you meet and talk with my sister, Mrs. Grey; she'sa Wellesley graduate," said Taylor, finally.

Mrs. Grey was delighted. It was a combination which she felt she needed.Here was a college-girl who could direct her philanthropies and heretiquette during the summer. Forthwith Mary Taylor received anintimation from her brother that vast interests depended on her summervacation.

Thus it had happened that Miss Taylor came to Lake George for hervacation after the first year at the Smith School, and she and MissSmith had silently agreed as she left that it would be better for hernot to return. But the gods of lower Broadway thought otherwise. Notthat Mary Taylor did not believe in Miss Smith's work, she was toohonest not to believe in education; but she was sure that this was nother work, and she had not as yet perfected in her own mind any theory ofthe world into which black folk fitted. She was rather taken back,therefore, to be regarded as an expert on the problem. First her brotherattacked her, not simply on cotton, but, to her great surprise, on Negroeducation; and after listening to her halting uncertain remarks, hesuggested to her certain matters which it would be better for her tobelieve when Mrs. Grey talked to her.

"Interested in darkies, you see," he concluded, "and looks to you totell things. Better go easy and suggest a waiting-game before she goesin heavy."

"But Miss Smith needs money--" the New England conscience prompted. JohnTaylor cut in sharply:

"We all need money, and I know people who need Mrs. Grey's more thanMiss Smith does at present."

Miss Taylor found the Lake George colony charming. It was notultra-fashionable, but it had wealth and leisure and some breeding.Especially was this true of a circumscribed, rather exclusive, set whichcentred around the Vanderpools of New York and Boston. They, or ratherMr. Vanderpool's connections, were of Old Dutch New York stock; hisfather it was who had built the Lake George cottage.

Mrs. Vanderpool was a Wells of Boston, and endured Lake George now andthen during the summer for her husband's sake, although she regarded itall as rather a joke. This summer promised to be unusually lonesome forher, and she was meditating a retreat to the Massachusetts north shorewhen she chanced to meet Mary Taylor, at a miscellaneous dinner, andfound her interesting. She discovered that this young woman knew things,that she could talk books, and that she was rather pretty. To be sureshe knew no people, bu

t Mrs. Vanderpool knew enough to even things.

"By the bye, I met some charming Alabama people last winter, inMontgomery--the Cresswells; do you know them?" she asked one day, asthey were lounging in wicker chairs on the Vanderpool porch. Then sheanswered the query herself: "No, of course you could not. It is too badthat your work deprives you of the society of people of your class. Nowmy ideal is a set of Negro schools where the white teachers _could_ knowthe Cresswells."

"Why, yes--" faltered Miss Taylor; "but--wouldn't that be difficult?"

"Why should it be?"

"I mean, would the Cresswells approve of educating Negroes?"

"Oh, 'educating'! The word conceals so much. Now, I take it theCresswells would object to instructing them in French and in dinneretiquette and tea-gowns, and so, in fact, would I; but teach them how tohandle a hoe and to sew and cook. I have reason to know that people likethe Cresswells would be delighted."

"And with the teachers of it?"

"Why not?--provided, of course, they were--well, gentlefolk andassociated accordingly."

"But one must associate with one's pupils."

"Oh, certainly, certainly; just as one must associate with one's maidsand chauffeurs and dressmakers--cordially and kindly, but with adifference."

"But--but, dear Mrs. Vanderpool, you wouldn't want your children trainedthat way, would you?"

"Certainly not, my dear. But these are not my children, they are thechildren of Negroes; we can't quite forget that, can we?"

"No, I suppose not," Miss Taylor admitted, a little helplessly. "But--itseems to me--that's the modern idea of taking culture to the masses."

"Frankly, then, the modern idea is not my idea; it is too socialistic.And as for culture applied to the masses, you utter a paradox. Themasses and work is the truth one must face."

"And culture and work?"

"Quite incompatible, I assure you, my dear." She stretched her silkenlimbs, lazily, while Miss Taylor sat silently staring at the waters.

Just then Mrs. Grey drove up in her new red motor.

Up to the time of Mary Taylor's arrival the acquaintance of theVanderpools and Mrs. Grey had been a matter chiefly of smiling bows.After Miss Taylor came there had been calls and casual intercourse, toMrs. Grey's great gratification and Mrs. Vanderpool's mingled amusementand annoyance. Mrs. Grey announced the arrival of the Easterlys and JohnTaylor for the week-end. As Mrs. Vanderpool could think of nothing lessboring, she consented to dine.

The atmosphere of Mrs. Grey's ornate cottage was different from that ofthe Vanderpools. The display of wealth and splendor had a touch of thebarbaric. Mary Taylor liked it, although she found the Vanderpoolatmosphere more subtly satisfying. There was a certain grim powerbeneath the Greys' mahogany and velvets that thrilled while it appalled.Precisely that side of the thing appealed to her brother. He would haveseen little or nothing in the plain elegance yonder, while here he saw aJapanese vase that cost no cent less than a thousand dollars. He meantto be able to duplicate it some day. He knew that Grey was poor and lessknowing than he sixty years ago.

The dead millionaire had begun his fortune by buying and sellingcotton--travelling in the South in reconstruction times, and sending hisagents. In this way he made his thousands. Then he took a step forward,and instead of following the prices induced the prices to follow him.Two or three small cotton corners brought him his tens of thousands.About this time Easterly joined him and pointed out a new road--thebuying and selling of stock in various cotton-mills and other industrialenterprises. Grey hesitated, but Easterly pushed him on and he made hishundreds of thousands. Then Easterly proposed buying controllinginterests in certain large mills and gradually consolidating them. Theplan grew and succeeded, and Grey made his millions.

Then Grey stopped; he had money enough, and he would venture no farther.He "was going to retire and eat peanuts," he said with a chuckle.

Easterly was disgusted. He, too, had made millions--not as many as Grey,but a few. It was not, however, simply money that he wanted, but power.The lust of financial dominion had gripped his soul, and he had a visionof a vast trust of cotton manufacturing covering the land. He talkedthis incessantly into Grey, but Grey continued to shake his head; thething was too big for his imagination. He was bent on retiring, and justas he had set the date a year hence he inadvertently died. On the whole,Mr. Easterly was glad of his partner's definite withdrawal, since heleft his capital behind him, until he found his vast plans about to becircumvented by Mrs. Grey withdrawing this capital from his control. "Togive to the niggers and Chinamen," he snorted to John Taylor, and strodeup and down the veranda. John Taylor removed his coat, lighted a blackcigar, and elevated his heels. The ladies were in the parlor, where thefemale Easterlys were prostrating themselves before Mrs. Vanderpool.

"Just what is your plan?" asked Taylor, quite as if he did not know.

"Why, man, the transfer of a hundred millions of stock would give mecontrol of the cotton-mills of America. Think of it!--the biggest trustnext to steel."

"Why not bigger?" asked Taylor, imperturbably puffing away. Mr. Easterlyeyed him. He had regarded Taylor hitherto as a very valuable asset tothe business--had relied on his knowledge of routine, his judgment andhis honesty; but he detected tonight a new tone in his clerk, somethingalmost authoritative and self-reliant. He paused and smiled at him.

"Bigger?"

But John Taylor was dead in earnest. He did not smile.

"First, there's England--and all Europe; why not bring them into thetrust?"

"Possibly, later; but first, America. Of course, I've got my eyes on theEuropean situation and feelers out; but such matters are more difficultand slower of adjustment over there--so damned much law and gospel."

"But there's another side."

"What's that?"

"You are planning to combine and control the manufacture of cotton--"

"Yes."

"But how about your raw material? The steel trust owns its iron mines."

"Of course--mines could be monopolized and hold the trust up; but ourraw material is perfectly safe--farms growing smaller, farms isolated,and we fixing the price. It's a cinch."

"Are you sure?" Taylor surveyed him with a narrowed look.

"Certain."

"I'm not. I've been looking up things, and there are three points you'dbetter study: First, cotton farms are not getting smaller; they'regetting bigger almighty fast, and there's a big cotton-land monopoly insight. Second, the banks and wholesale houses in the South _can_ controlthe cotton output if they work together. Third, watch the Southern'Farmers' League' of big landlords."

Mr. Easterly threw away his cigar and sat down. Taylor straightened up,switched on the porch light, and took a bundle of papers from his coatpocket.

"Here are census figures," he said, "commercial reports and letters."They pored over them a half hour. Then Easterly arose.

"There's something in it," he admitted, "but what can we do? What do youpropose?"

"Monopolize the growth as well as the manufacture of cotton, and usethe first to club European manufacturers into submission."

Easterly stared at him.

"Good Lord!" he ejaculated; "you're crazy!"

But Taylor smiled a slow, thin smile, and put away his papers. Easterlycontinued to stare at his subordinate with a sort of fascination, withthe awe that one feels when genius unexpectedly reveals itself from asource hitherto regarded as entirely ordinary. At last he drew a longbreath, remarking indefinitely:

"I'll think it over."

A stir in the parlor indicated departure.

"Well, you watch the Farmers' League, and note its success and methods,"counselled John Taylor, his tone and manner unchanged. "Then figure whatit might do in the hands of--let us say, friends."

"Who's running it?"

"A Colonel Cresswell is its head, and happens also to be the forcebehind it. Aristocratic family--big planter--near where my sisterteaches."

"H'm--well, we'll watch _him_."

/> "And say," as Easterly was turning away, "you know Congressman Smith?"

"I should say I did."

"Well, Mrs. Grey seems to be depending on him for advice in distributingsome of her charity funds."

Easterly appeared startled.

"She is, is she!" he exclaimed. "But here come the ladies." He wentforward at once, but John Taylor drew back. He noted Mrs. Vanderpool,and thought her too thin and pale. The dashing young Miss Easterly wasmore to his taste. He intended to have a wife like that one of thesedays.

"Mary," said he to his sister as he finally rose to go, "tell me aboutthe Cresswells."

Mary explained to him at length the impossibility of her knowing muchabout the local white aristocracy of Tooms County, and then told him allshe had heard.

"Mrs. Grey talked to you much?"

"Yes."

"About darky schools?"

"Yes."

"What does she intend to do?"

"I think she will aid Miss Smith first."

"Did you suggest anything?"

"Well, I told her what I thought about cooeperating with the local whitepeople."

"The Cresswells?"

"Yes--you see Mrs. Vanderpool knows the Cresswells."

"Does, eh? Good! Say, that's a good point. You just bear heavy onit--cooeperate with the Cresswells."

"Why, yes. But--you see, John, I don't just know whether one _could_cooeperate with the Cresswells or not--one hears such contradictorystories of them. But there must be some other white people--"

"Stuff! It's the Cresswells we want."

"Well," Mary was very dubious, "they are--the most important."

The Quest of the Silver Fleece: A Novel

The Quest of the Silver Fleece: A Novel